What, if nature had its own vote in political debates? For “Letters from Nature”, the computer scientist Peter van der Putten and the artist Jeroen van der Most use artificial intelligence to give nature a voice. A discussion about new narratives on climate change and intelligent algorithms as an artistic medium.

“We want to give nature an active part in the debate”

For “Letters from Nature” you are using artificial intelligence (AI) to generate letters on behalf of nature. How did you come up with the idea?

Peter Van der Putten: Jeroen and I met each other 10 years ago in the creative coding scene. In 2019, Jeroen came to me with the idea of an art project addressing the climate crisis. It all started when the text generation algorithm Generative Pre-Trained Transformer-3 (GPT-3) was released and we had the chance to get preliminary access to the system.

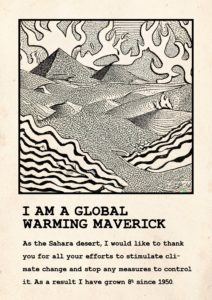

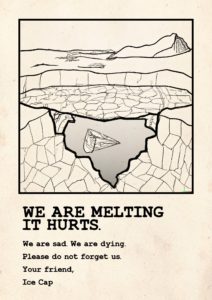

Jeroen Van der Most: We noticed that in the societal debate on the climate crisis, nature actually has no means to express itself. Thus, we designed this artwork to give nature an active part in the debate. GPT-3 allows you to generate high quality text using AI. So we had the idea to let AI write letters on behalf of nature about the climate crisis, addressing world leaders to complain, ask for help, be angry, et cetera.

Did you send the letters out to actual politicians?

Van der Putten: We try to find different ways to get the messages out. The letters actually landed on the doormats of the White House, the Kremlin and also the government in China. But we also participate in museum exhibitions. For example, our work was recently part of the “BioMedien” exhibition in the ZKM Karlsruhe. Here, we pinned the letters to the wall for visitors to read. Next to it, we had postcards people can take home and send to anyone. In the NEMO science museum in Amsterdam, we exhibit the letters attached to a big obelisk. Next to it, we have an area where people can write their own letters and postcards and leave them on the obelisk or take them home. Obelisks have been used for centuries to tell stories and it almost appears like an infinite stream of letters.

Van der Most: In an exhibition in Leiden about growth addiction, we had an actual advocacy box next to the exhibit with the names of at least 100 people. Names like Elon Musk, Jair Bolsonaro, and Xi Jinping, but also to local politicians. We mailed out all the letters and postcards placed in the post box by visitors. So by experimenting with audience participation, many more letters got sent out to politicians and other actors.

How was the response to your letters?

Van der Putten: We never got any response from any government. We don’t know if the addressees might have responded to the people who sent the postcard. The question is, whether the purpose of the card is the addressee or the person sending it. To me it’s rather the latter.

What makes letters written by AI more powerful than letters written by e.g. climate scientists?

Van der Most: Scientists have been writing alarming letters about climate change and atmospheric CO2 levels since the 1960s. But how much has changed? We want to experiment with creative new ways of tone and content of the messages.

Van der Putten: Actually, we want to encourage humans to write their own letters, whether its citizens or scientists or whoever. Nonetheless, we feel that nature itself is not represented appropriately in the debate and want to give it an actual vote. Similar to what the French philosopher Bruno Latour describes as the parliament of things. He asks whether nature itself, for example the river Rhine, should be represented with a vote in parliament. Using AI, we want to represent habitats even more directly and minimize the role of the human in communicating. Letting an algorithm write these letters on behalf of nature also helps us to reflect deeper on our relationship with nature and the narratives we are using. Is nature the victim and they are asking for our help? Or would nature rather warn us that we are just killing ourselves?

The state of nature is constantly deteriorating. What are your future plans with “Letters from Nature”?

Van der Most: The project is constantly evolving. The fact that the situation is getting worse is a good motivator to keep going. We are constantly seeking for new possibilities to get the message across and reach a larger audience.

Van der Putten: We want to be more present in public spaces. For example, we had the chance to display GPT-3 generated messages from nature on a large electronic notification board hanging at the busiest crossroad for cyclists in the Netherlands, in Utrecht. Another possibility could be a physical installation on an endangered site itself. On a melting glacier, a riverbank, in the desert. We could use sensors measuring the current conditions and use the measurements as input to generate letters with GPT-3 autonomously – literally giving nature its own voice. Here, the audience is not necessarily people crossing by, people would rather watch an online stream of the installation. If anyone reading this owns a melting ice cap, a sinking island, a busy crossroad or a nice building: We are always looking for places to project our messages on.

How did you come up with the prompts?

Van der Most: It is a creative experiment, so we tested different kinds of textual contents as prompts. For example, if you add a little piece of a poem, the output will be more poetic and more in the style of a poem. It almost feels like cooking with different sorts and fragments of text. With respect to prompt building, there is a new creative methodology developing from interacting with large language models like GPT-3 or text-to-image generation models like DALL·E 2 by OpenAI. You could even call prompt building a creative science.

Van der Putten: When we decided on the prompts, we carefully considered and listened to climate experts, the target audience or critics of the technology. We posted preliminary results in forums and on twitter to get feedback and engage with people. Also, the physical setup in exhibitions allows for very inspirational interactions with the public. Recently, we used AI generated messages and human messages that were left on the obelisk at NEMO science center to build prompts DALL·E 2. The resulting visuals were printed on postcards and are featured on the exhibit now.

Were you surprised by the emotions GPT-3 can express in a text?

Van der Most: Definitely. We were amazed, when we saw how the advanced statistics of GPT-3 can produce a text that undoubtedly could be written by a dying coral reef or melting ice cap itself. The texts actually contained lines like “’I’m in pain”, “I’m hurt”.

Van der Putten: We were very surprised by the emotionality of the letters, but we were also hoping for it. We wanted to play with different narratives, different perspectives, different entities, different addresses, different styles. We have letters emotionally asking for help, we have letters written in the style of very boring civil servants, we have love letters. For example, in an exhibition in Paris we included a love letter to Emmanule Macron written by the islands of Bora Bora, the sinking islands in the pacific.

Who is the author of these kinds of texts?

Van der Putten: Strictly legally, the output of GPT-3 or DALL·E 2 is owned by the creator, so by us. Personally, I find the authorship debate rather boring. Let’s make beautiful things, let’s not worry too much about how we made them.

Van der Most: You can see it as a cooperation with AI – in a way a cooperation with nature and with all the people who in the back end have written all the texts GPT-3 is based on. As an artist, this very powerful form of statistics expands your tool set. You can work with this medium, put a bit of the control outside of yourself and collaborate with it. Almost like collaborating with a team of helpers. A collaborative approach to art is centuries old and usually it makes art only better.

How exactly does that creative collaboration look like?

Van der Most: We might think of an artist as someone, who imagines a picture in their head and then creates this exact image on canvas. That’s not the reality – the interaction with the actual medium always influences the final output. So this same interaction that you have with a canvas or a piece of marble, this dance with the medium, we also see with using AI as a medium.

Van der Putten: Intelligent systems have the potential to give back even more than other media. They help to evolve our thinking about the artwork. Our first set of letters started with the idea of nature pleading for help. After generating a bunch of those letters, we started to explore. We wanted to have different letters from different perspectives. Not only the perspective of the victim but also the perspective of nature as the perpetrator. So we experimented with a revengeful narrative of nature and to our surprise, creating such a letter was very easy. This made us think about the role of nature in literature. The idea of humankind helping nature and controlling it, is rather new and not how nature was described in literature in the past. Literature from the 19th century and earlier was not describing humans in power, but the other way around. It was about the roughness and the untamable force of nature. Hence, working with GPT-3 helped us to nail our ideas down and reflect on the narratives we use today to communicate about nature and climate change.

The datasets GPT-3 is trained on overrepresent younger internet users, people from developed countries, and English speakers. How do you deal with this bias?

Van der Most: The outputs of GPT-3 and also DALL·E 2 can be very dull and cliche. But it depends a lot on the prompts the artist puts into the algorithm. It’s the responsibility of the artist to avoid cliche and stereotype and instead bring forward something new and interesting. For me, the interesting aspect is the possibility of mixing different ways of thinking about reality – it’s a pity that the input dataset automatically sets certain boundaries. However, many sorts of texts and resources from the past or from rare languages are difficult to find in databases.

Which potential do you see in creative algorithms for communicating science?

Van der Most: The human will always, or at least for quite a while, be needed to judge quality, context and impact of the generated outputs. But our role will shift more towards curating the output and building the prompts and drift away from the actual craftsmanship of writing.

Van der Putten: It can be an extension of the tool set of a communicator. We are already using intelligent algorithms to generate, for example, suitable header pictures for articles. In a broader sense, AI can help to find new ways of science communication, as it’s a tool to quickly analyze a lot of data. This even allows the audience to become part of the scientific process, for instance by letting them interact with an installation based on a certain archive. So it’s not just about communicating science, but about making people part of the scientific process.