Is a global center going to revolutionize science communication? An interview with science communication experts Jenni Metcalfe and Toss Gascoigne, who emphasize the importance of diverse cultures, knowledge systems, and inclusive approaches.

Unlocking the Potential of Global Science Communication

Why is a global perspective on science communication important?

Jenni Metcalfe: Well, I think it is important because there are so many different cultures and ways of approaching science communication. There are different histories of science communication. And that diversity gives a richness but it also gives the possibility to make comparisons. Which can help the learning between countries and between regions.

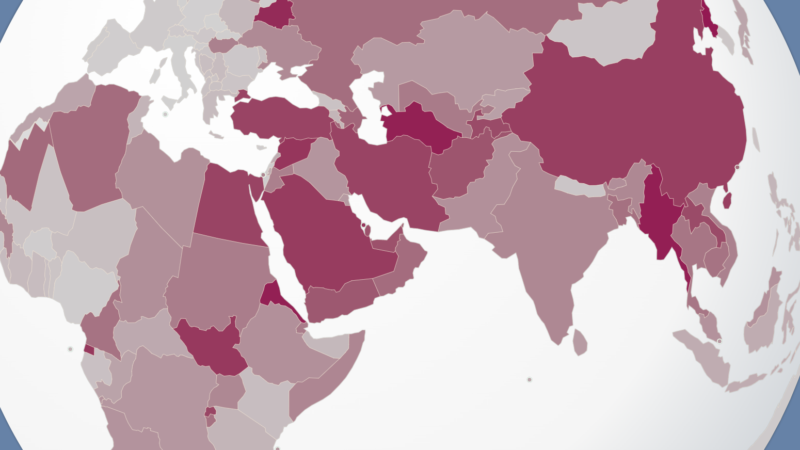

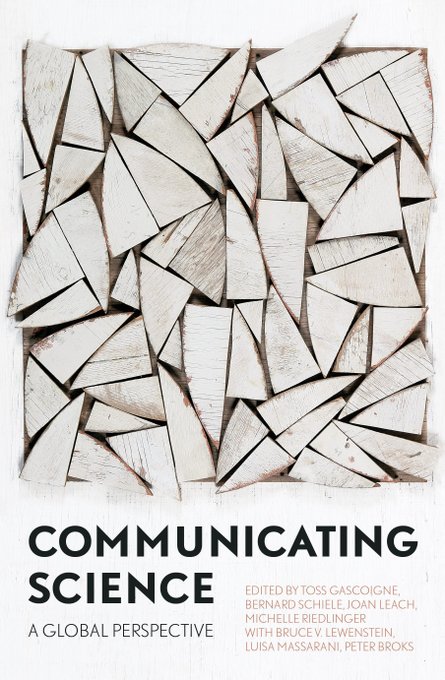

Toss Gascoigne: “Communicating Science“ documents the way modern science communication emerged across 39 countries. It shows similarities among countries in Western Europe and richer nations, but different concerns and needs in African, Asian, and South American countries. Islamic majority states like Iran, Pakistan, Malaysia, Nigeria, and Turkey provide unique perspectives where religion played a role in shaping views on science-based issues. We can learn from each other, especially regarding climate change, COVID treatment, industrialization, and leveraging scientific research for national economies. Overall, there are unifying factors and a trend of closer collaboration.

Communication of Science and Technology, and helped make PCST a truly international body. He was chief editor of ‘Communicating Science. A Global Perspective‚. Photo: Toss Gascoigne

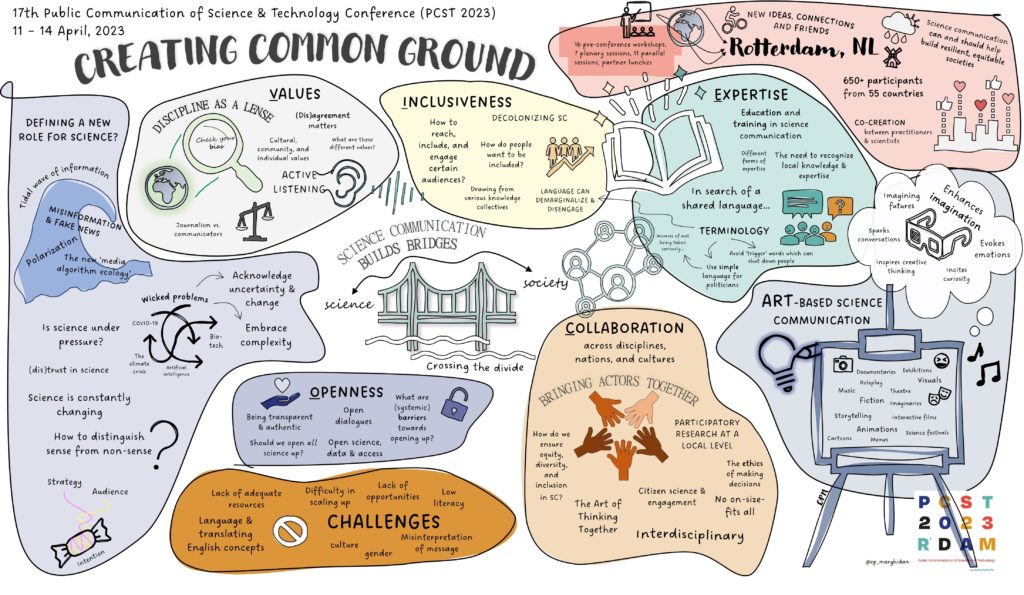

The topic of the latest International Network on Public Communication of Science and Technology (PCST) meeting in Rotterdam was „Creating Common Ground.“ Some of the identified challenges included translating concepts into English, resource limitations, and difficulties with scaling up. What strategies does the network propose to overcome these obstacles?

Gascoigne: Through my experiences with politicians and policymakers, I’ve observed that they often possess a simplistic understanding of science communication, its role, and its value. Many believe that the primary task of science communicators is to disseminate more and more information. Unfortunately, they fail to recognize that populations themselves have knowledge and expertise to contribute. Engaging in meaningful dialogue and actively listening to the public’s perspectives remain relatively rare and sophisticated actions for policymakers.

Regarding the challenges and their resolution, I believe there are primarily two significant barriers to address. The first pertains to cultural differences, especially the language barrier. The second barrier involves the division between the natural sciences, and the humanities and social sciences, particularly in countries influenced by Great Britain. In contrast, parts of Europe adopt a more integrated perspective, acknowledging the interconnectedness of research in these areas.

Metcalfe: I’m uncertain if the English concepts of science communication are necessarily the most appropriate. Currently, there is discourse and published papers addressing the colonization of Western science and Western science communication in countries with their own existing knowledge and epistemologies. Thus, we need to seriously consider whether the dominant English paradigm of science communication is truly the most suitable for sharing in the first place. We have much to learn from Africa, India, China. Adopting such an arrogant viewpoint, assuming that the English approach is correct, is problematic.

Do you think the global scicomm community can profit from integrating indigenous perspectives?

Gascoigne: I believe it is crucial.

Metcalfe: That is what I meant when I said we can learn from other countries, knowledge systems, and communication methods that go beyond the traditional roots in the UK and Europe.

Gascoigne: I was delighted to receive chapters in Communicating Science from Islamic majority countries. The significant contributions of Islamic sciences over the past 1000 years are often overlooked, possibly due to the language barrier and a superiority complex held by some Western countries

At the same meeting in Rotterdam you hosted a roundtable discussion on whether there should be a global center for science communication. What speaks for such a global center?

Metcalfe: There is a sense that having a center dedicated to exploring the ideas we’ve been discussing would be beneficial. It would bring together scholars and practitioners from diverse cultures and experiences in science communication, fostering mutual learning. Much of the discussion focused on how the center would be established—whether virtual or physical—and what its specific goals and functions would be. Most participants recognized the benefits of having a center that could provide advice to global policymakers and give science communicators a voice and a platform. While there were perceived benefits, the challenge lies in funding, setting up, and ensuring the center delivers on its promises to our community.

Gascoigne: This discussion should be seen as just the beginning. The idea was initially proposed by Melanie Smallman in the UK. We became interested, formed a panel, and discussed various aspects in Rotterdam. The discussion boiled down to five key ideas: purpose, functions, location, activities, and collaboration. As the conversation progressed, it became evident that we were at the early stages of shaping the center’s form and function. Conducting an audit of existing science communication centers worldwide – identifying their scope, funding, staffing, and activities – would be a useful starting point. This could lead to the formation of a network or linked group of centers worldwide that agree on common agendas and pursue shared issues to support national science communication centers.

Do you have any other activities in mind that a global center could pursue? Perhaps related to the equitable distribution of resources globally.

Metcalfe: I believe a center, like the one we discussed in Rotterdam, would play a crucial role in policymaking at both multilateral and national levels. It would provide support to developing countries that need to present a value proposition for a different style of science communication. Resource allocation and availability would be important considerations. The United Nations, for instance, has expressed interest in a body like this that can contribute to their discussions and decision-making processes at the global level. There are significant opportunities for a center like this to make a coherent and meaningful impact on the perception and implementation of advanced and progressive science communication.

Gascoigne: One idea that Melanie raised was the concept of capturing knowledge. She was concerned that valuable ideas often fade away and are forgotten. A center could serve as a repository of ideas, not quite like a library, but a shared space where people can draw upon and exchange ideas. It is essential to carefully consider the nature of such a center because different countries have sharply contrasting concerns. Taking Denmark and Kenya as an example: Denmark might focus on the democratization of science, actively involving the public in research decision-making processes and resource allocation. On the other hand, Kenya’s concerns are more practical, such as working out solutions for pregnant women in remote communities who struggle to reach hospitals for childbirth. This is an over-simplification but it illustrates that the concerns and approaches to science communication differ greatly across countries, reflecting varying stages of development, priorities, and perspectives.

You both play active roles within the PCST network. I’m curious, do you think the PCST Network could serve as a global center for science communication, or is that not feasible from an organizational standpoint?

Metcalfe: Currently, the network heavily relies on voluntary work. However, it may be time for PCST to consider establishing a more institutional foundation. In that sense, it could potentially serve as the basis for such a center, or at the very least, become a major sponsor or provide a governing board. There are possibilities for it to be the epicenter or a supporting entity of a global science communication center.

Gascoigne: The organization has gradually gained momentum, becoming more sophisticated with longer conferences, workshops, and webinars. PCST is a influential gathering for science communication practitioners and researchers but we don’t have the funds for a secretariat. The Kavli Foundation in the United States has provided significant support for our recent conferences and the upcoming one in Aberdeen. It will require hard work and thoughtful planning by the current committee members to navigate the path from our current stage to the next, which could involve hiring an executive officer. Everything is possible.

And finally, let’s look into the crystal ball: What global trends in science communication do you think will become more relevant in the coming years?

Metcalfe: I believe the most significant trend is recognizing the interconnectedness of different models of science communication and understanding their mutual dependence and importance in achieving our goals. This includes effectively disseminating clear and accurate messages, fostering dialogue and engagement, and promoting participation in science. All these aspects are intertwined in today’s science communication landscape. Another emerging trend, which may present challenges, is shifting our focus from science communication to knowledge communication. We should move beyond the confines of Western Science and embrace a more inclusive approach to different knowledge systems and how we communicate about them.