Are we overlooking a fundamental human right: the right to science? According to Sujatha Raman, science communication could protect researchers worldwide from attacks.

Science is a human right – but what does that mean?

Ms. Raman, you hold the UNESCO Chair in Science Communication for the Public Good. What are the goals of your group?

The UNESCO Chair aims to promote inclusive ways of thinking about the role of science, technology and innovation in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. We want to go beyond top-down approaches and, for example, address concerns about the impact of emerging technologies. We are also thinking about science policy, science to science communication and integration to bring social science and natural science perspectives together.

Who determines what constitutes the public good?

It’s not easy to define. It can be seen as either a top-down directive or as an aggregation of individual interests. I’m interested in broadening that perspective to look at what we all have in common as inhabitants of the same planet. In our polarised world, finding common ground is crucial. So, to answer your question, defining the public good is complex and needs more discourse and exploration. We are currently organizing workshops to delve deeper and bring the subject to the forefront of the conversation.

Perhaps a human rights perspective can provide a common language, a basic set of shared values and morals?

Yes, I agree. It’s a promising approach to translate the concept of the common good based on principles of rights.

Many human rights are related to basic needs – like food and shelter. But in which way can science be conceptualized as a fundamental human right?

The right to science emphasizes the link between those basic needs, and other things like freedom of opinion, expression, and movement, and access to knowledge. A human rights perspective expands the traditional view of science beyond the confines of the lab and shows its relevance to broader goals of sustainable development. That means that the public has a right to have a say in how research is designed. So that potential risks are anticipated, but there’s also an effort to work towards more equitable outcomes. It also means supporting the right of some communities to say no to modern technologies or to promote their own ideas about how to live more sustainably.

Article 27 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that „everyone has the right […] to share in scientific progress and its benefits“. Why is there so little knowledge about the “right to science”?

While there has been some scholarly reflection on the right to science, it has mostly been in a legal context. The United Nations understandably prioritize addressing immediate needs such as shelter and food security, which can overshadow discussions of the right to science. I wonder if another reason why it hasn’t attracted much attention is that it would be very easy to read it in a rather one-sided way. It could be read to mean that science produced by experts is just passively received by the rest of us, in terms of a deficit model that we as a field have done so much to criticize.

But I’m optimistic about the right to science. The time is ripe to take up these laws and interpret them in the light of current discussions. I hope that through events like our conference in June we can create more awareness about what it means to put this right into practice.

Researchers often argue that they owe science communication to the public as their work is funded by taxpayers‘ money. How does a human rights perspective broaden this view?

The argument is valid, but somewhat narrow. While taxpayers are entitled to science communication, a broader perspective is that society is made up of individuals with many different backgrounds. Engaging with all the people of the community, including those who do not pay taxes, do not vote or who aren’t citizens, enriches our practice of science communication. A human rights perspective allows us to move past a narrow economic view, so that we can address the diverse needs of society.

It’s really important to bring different epistemic voices and knowers into the conversation. We often find ourselves making this argument, stressing the importance of inclusion in science communication. And we’ve been doing that in the field for many years. The human rights framework can help us to better articulate the reasons for these arguments.

Following growing interest in the right, the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights added more context in 2020. States are obligated to “take steps for […] the diffusion of science”. How can it be monitored if states fulfill their obligation to promote science communication?

I would step back and ask how scientists are perceived in relation to the state. And in relation to their communities. If science is seen as an elite activity, disconnected from everyday life, it becomes difficult to mobilize public demand for the state to fulfill this responsibility.

However, there are opportunities for scientists to form alliances with communities to put pressure on the state. We can harness these alliances and ensure that the science communication is not only widespread but also beneficial. But taking steps to disseminate science should not be confused with promoting science as the solution to complex social or environmental problems. Indeed, science communication can play a key role in fostering discussion of what science cannot give us as well as what it can .

Volker Türk, the UN high commissioner for human rights, recently wrote: “Too many governments, policymakers and big-industry leaders are wilfully shutting their eyes to science”. Do you have any examples of alliances of scientists and local communities working together to put pressure on state actors?

A well-known case is Flint, Michigan, where thousands of people were exposed to dangerous levels of lead in their drinking water. The Flint community’s collaboration with scientists, journalists, doctors and activists ultimately exposed the city’s gross mismanagement of its drinking water. Similar partnerships exist around the world, where scientists work with communities to collect data on pollution and its effects. These efforts are documented in resources such as the Environmental Justice Atlas, which highlights many cases of environmental justice initiatives.

Are there cases where scientific progress conflicts with the protection of human rights?

One example is the case of the Thirty Meter Telescope project in Hawaii. This telescope, which was supposed to advance astronomical research, sparked controversy because it was to be built on land sacred to Indigenous communities. While astronomers argue for its benefits to scientific progress, Indigenous groups argue for the protection of their sacred land rights. This is obviously a clash between an absolutist understanding of the right to scientific progress and the human rights of Indigenous peoples.

Europe’s highest human rights court has just ruled: protecting the climate is a human right. What strategies can environmental communication employ to protect this human right?

The decision carries weight in addressing the pressing issue of climate change. But it’s not just about court cases; it’s about how we communicate about the environment every day. We need to have conversations that go beyond courtrooms and headlines.

For example, when we talk about the transition to cleaner energy, it’s not just about switching from fossil fuels to renewables. We need to address the deeper complexities of our energy systems and consumption patterns. Yes, we have to stop using fossil fuels. And we have to move to other ways of generating energy. But we also know that what is described as clean energy is also having environmental and social impacts, with the mining of minerals for example.

That’s where environmental communication comes in. It’s about fostering a deeper understanding of the systemic changes needed to protect our planet. To advance climate action as a human right, we need to marry legal principles with community based dialogue.

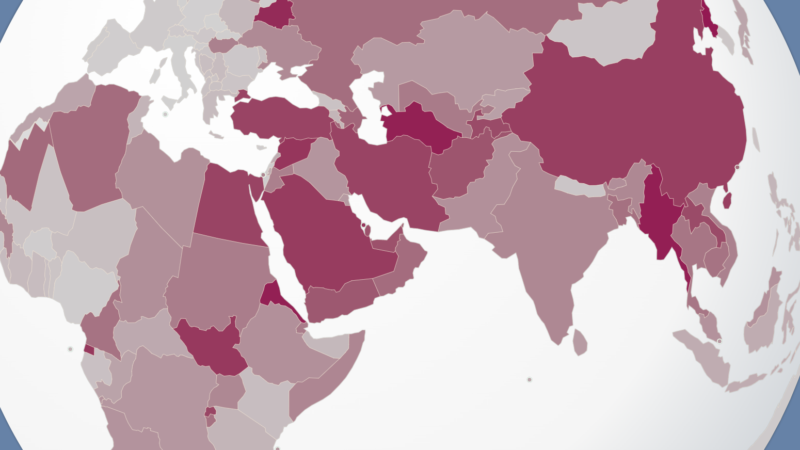

There are growing attacks on scientists around the world. Is there a role for science communication in addressing these threats?

Absolutely, science communication has a crucial role to play in addressing these threats. Last year, I was part of a panel discussion on attacks on scientists organised by the International Science Council. Perhaps one of the best contributions that science communication can make to these issues is to advance the way we think about science and what we can expect from it.

For example, it can help us move away from expecting clear-cut answers to complex questions. It can highlight the nuances of scientific inquiry and reduce the burden on scientists. I think a lot of these attacks on scientists are almost driven by the expectation that you should get a simple answer, or if you’ve given the ‚wrong‘ answer, then you should be attacked.