Ever danced about endangered turtles? Marine scientist and dancer Lekelia Jenkins unites art and science by creating dances that visualize research topics. In this interview, she explains how every science topic can be turned into a dance, and why it was a hard road to be accepted as both a dancer and a scientist.

“Science and Art are not enemies”

As a marine scientist and dancer, you are interested in the intersection of science and dance as a tool to communicate research findings and engage the community in research projects. But what exactly is Science Dance?

Science dance is something that’s still evolving and it can be many things. It is not only science communication. There are artists and choreographers who do science dance in the high art sense, where science is their muse, science is what inspires their ideas, but the dance is in its own right and is art in its own right. I use science dance for engagement and to get people involved in issues they wouldn’t normally be involved in.

How do you develop a dance about a scientific topic?

My workshops are mainly attended by university students and researchers, but also people from outside the university. Together we create a dance about a research topic. I call my process SciDance, it is a participatory co-created choreography. So I don’t come in and say: “Here are my movements”. I make sure that I have cornerstones of support that I know will drive the story, activities that I know will translate very well. Like body surfing. It is a lot of fun. You get four or five people very close together on the floor, rolling in unison. Especially if they’re wearing blue costumes, everyone immediately understands that these are ocean waves. You can put one person on top and literally move them back and forth. If that person is green, it looks like a dead turtle.

At the end of maybe two hours, we have created a five-minute dance. This process of creating and dancing helps the scientists to get more in touch with their own research. The citizens who take part are exposed to subjects that they would not otherwise have been exposed to. This sea turtle dance, opened up the discussion about why turtles are dying and what we can do about it.

Dancing is something personal and not everyone is used to it. Also, the participants do not know each other. What is important when leading such a group?

Each group has its own identity, a place of comfort with their own bodies and with each other. It’s a delicate balance to push them. You want to push people towards new ideas, but you don’t want to make them uncomfortable. So part of what I do is read the group, how comfortable they are, push them to the edge of new discovery, but then bring them back to a safe place and push them again. Even people who say “I’m not a mover” end up being amazed.

Do you think a science dance works with all scientific topics?

It’s possible with any science topic, but some are definitely easier than others. Not everyone knows for instance what a mass spectrometer is. So you might have to spend some time unpacking what that word means and a little bit more prep work, but in the end also a dance about a mass spectrometer is possible. I’ve been told that not all sciences entail movement. I don’t think that’s true. That’s the power of dance, you can take something that is hard for the human mind to grasp because the movement is so small, slow or distant, and represent it in something that people can see, and it creates an analogy for them to connect with.

During live events, I occasionally do a short exercise with the audience. I literally say to them: give me the title of your latest publication and we will make a dance out of it.

Although it was challenging, we managed to make a dance out of all of them. We only had 10 or 15 minutes with one group of dancers. When I do not have much time, I look for an idea that intrinsically has movement in it, that has vivid words that people automatically grasp.

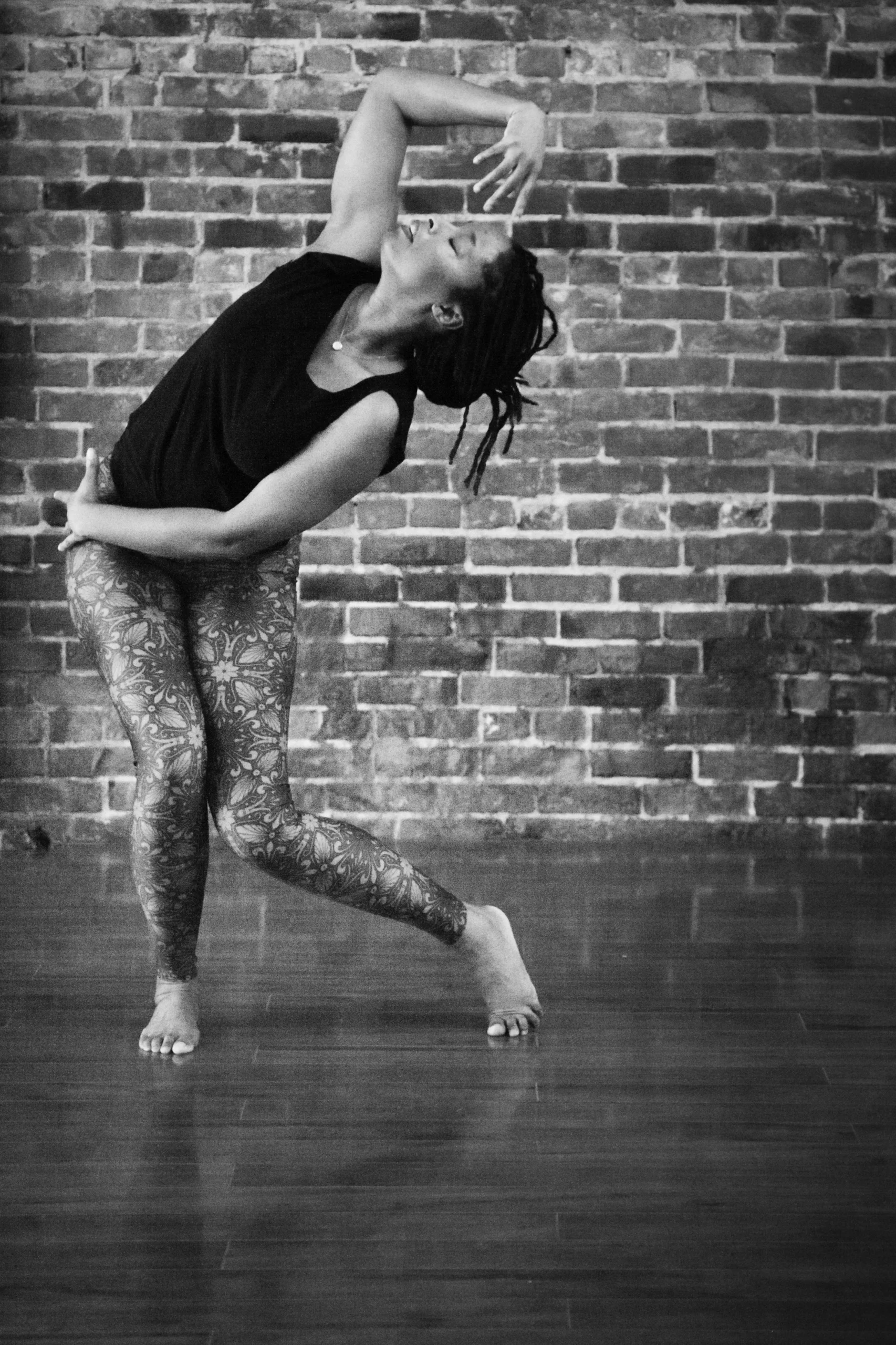

Lekelia Jenkins leads a workshop. Participants perform a dance about sea turtles. Picture: Private

Participants perform a dance about sea turtles.Picture: Private

Participants perform a dance about sea turtles.Picture: Private

Why is art, and dance in particular, a good way of engaging with people in the context of science?

150 years ago, you could not be a scientist of nature if you could not draw what you saw. DaVinci was a scientist, an engineer and an artist. But in the early 1900s, these two disciplines began to diverge. Art was seen as the antithesis of science, the artistic mind was seen as different from the scientific mind. In my opinion this is not true, science and art are not enemies. In our culture in the United States, art is accepted as a vehicle for learning, but only up to a certain point. In the third grade, you can have songs about the solar system or the nitrogen cycle, but then it has to stop.

Science Dance for adults provides a safe space for learning to express science through song and movement. We have cultures around the world that have preserved powerful oral histories through song and dance. They are very sticky. We’re just rediscovering something that, quite frankly, has been lost in the Western world in recent times. We’re bringing it back and rediscovering the power of it.

And what kind of power is that?

Science and art work in synergy. The power of science, music and art is a wonderful way for the brain to learn. But the last bit that makes it special for my cultural context is that it allows adults to give and receive touch in a safe, controlled, permissible way. I think it literally changes the biochemistry of our brains. We know that when you get a hug, you’re releasing all these positive chemicals into your body. And I think science dance does the same thing. When you get that great feeling from other people, you want to come back for it. You remember it. It becomes special because of how you felt, not just what you thought.

You said that art and science are perceived as two opposites. How were you accepted as a dancer and a scientist during your career?

It was not easy in the beginning. At school I was applying for graduate programmes and I asked my biochemistry teacher to write a letter of recommendation. I’ll never forget the letter she wrote. It began with the sentence “Kiki, when she entered my class, I knew she was a dancer, so I didn’t expect very much. But she turned out to be really brilliant in biochemistry.” That was the first time I realised that people view the arts and people who do arts as opposites: you can’t do both well. If you’re a good dancer, then you must be bad at science.

But I was also fortunate. My first summer in graduate school, I went to Duke University, which is home of the American Dance Festival. Although most students want to show off what a great scientist they are in their first summer, I realised: I can’t be here and not participate. I asked my advisor if he’d mind if I spent the summer doing dance instead of science.

He said to me: “Absolutely, that’s okay, because art feeds creativity and that will make your science better.” He understood that because he’s a trained drummer.

There were definitely people around me who thought it was not okay. I heard that message throughout my career until very recently.

You also started a science-art collective at The University of Washington, where science artists could meet and exchange ideas. What was your experience of these meetings?

The first few months of meetings were like a therapy group for science artists who were hiding in the closet. They did amazing work. One of them had a secret gallery show and none of his colleagues knew about it because he was worried about how they would view his science. You almost have to earn the right to make art and to communicate science through art, especially if you’re a very high-level research scientist: you’re maybe wasting too much of your time on that. This opinion is slowly changing, but too slow, in my opinion.

From your perspective as a science communicator linked to arts, how do you assess the development of science communication in recent years?

There’s this current fascination and obsession with social media. 15 years ago, science communication training prepared people for all sorts of venues. Now, in science communication training, it’s almost all about social media. As a science communicator, I’m worried that we’re not balancing our science communication portfolio well. Social media is tempting because it allows you to have some metrics of impact, but is that impact sustainable?

I think with social media you touch people, they have an awareness, but the face-to-face contact allows you to go really deep. If someone goes to work on Monday and a colleague asks how the weekend was, believe me, they are more likely to say: “I did a dance about sea turtles” instead of: “Oh, I saw this really interesting TikTok”.