Writing effectively and engagingly about complex science topics can sometimes feel like a dark art. The Open Notebook, a free and open online resource, shares the behind-the-scenes of science writing. A conversation with Siri Carpenter on writing, generative AI and the future of science journalism.

“Readers are not your hostages”

The Open Notebook is a nonprofit organization whose mission is to help journalists improve their science reporting skills. You offer a comprehensive library of articles on the craft of science journalism, as well as training and mentoring programs. Why did you found The Open Notebook?

When we started The Open Notebook in 2010, science journalism was going through a lot of turbulent change due to the financial models of the industry. That is not something that we as journalists could control—the profit models of science journalism. However, what we believed was that high-quality craftsmanship still mattered, and we wanted to focus our attention on the craft of science writing. And that’s what we have done.

What makes a great science story?

I think great science stories are those that reveal something about the scientific process and shed light on the world and how it functions. Whether it’s exploring the human mind, black holes, or the mechanisms of thermal vents at the ocean floor, these stories reveal the human process behind the science. Great science stories are intriguing, often surprising or controversial, they might be revealing something fascinating or previously not understood. They are original, breaking fresh ground and they are deeply rooted in evidence.

Would you encourage scientists to write about their own work?

Yes, many scientists find it highly rewarding. Scientists do this in various ways: they write commentaries and features providing a first-person perspective on the science, or publish popular science books about their work. Scientists who hold full-time jobs have a certain advantage over journalists in that they typically have a stable salary. They’re not depending on their science communication work to make a living.

As an experienced editor and writer, what changes can anyone writing about science make to their texts right now?

I believe it’s crucial for everyone to keep their audience in mind and see themselves as advocates for that audience. Consider what they already know, what interests them, and what they can easily comprehend. How dense should the material be? Can someone without expertise in the subject understand and enjoy it?

Most of the time, we’re discussing pieces of writing that aren’t mandatory reading. If the text is overly complex, confusing, dull, or filled with details that are significant to scientists but may bewilder general readers, they will simply stop reading. Readers are not your hostages. So, I think the key for anyone communicating about science is to prioritize the needs and preferences of the audience.

Should we use AI to improve our science writing – like spell checkers, translation tools, ChatGPT and such?

Everyday I get pitches from people who relied entirely on ChatGPT to write their pitches, and they are terrible. There is not a chance that I am going to assign those stories. I want to assign articles to humans, not to robots. So there are bad uses of generative AI, but I think that there are also very clever uses.

Obviously ChatGPT makes things up. You have to be really careful and not take anything that it says at face value. But it can be really valuable for helping trigger a mental process. I suspect that generative AI might open up some opportunities for science writers from the global south or those for whom English isn’t their first language. Not because they should have ChatGPT write their articles, but because it appears to be a powerful tool that can help level the playing field to some extent.

Speaking of turbulent changes in the industry – you offer a lot of resources for newcomers to science writing on The Open Notebook. How important is mentorship?

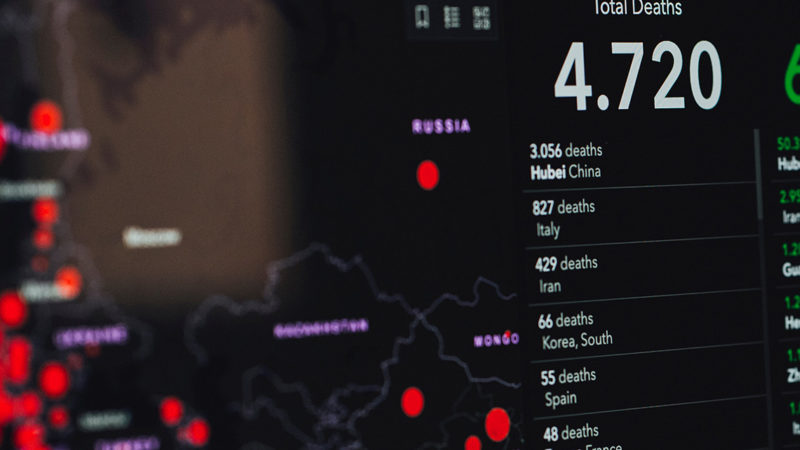

Mentorship is the most rewarding aspect of my job, and I believe many other science journalists feel the same way. It serves as an antidote to financial despair. However, there is an uncomfortable juxtaposition. The field is challenging, not just due to financial insecurity, but also the topics covered. Those who have spent the past few years reporting on COVID-19 have experienced a lot of burnout.

Yet, what motivates people to continue and mentor newcomers is the understanding that this work is critically important. Although it can be so difficult, it can also be phenomenally exciting to have a front row seat to watch science unfolding. It’s a continuing learning opportunity, lifelong growth. There is so much about science writing, the actual reporting and writing, that is existentially thrilling. Like any profession, you take the good with the bad.

Is there anything from your PhD training that you still apply in your work as a science journalism professional?

Yes, in many ways. My PhD was in social psychology, specifically I was studying implicit bias, prejudices, and stereotyping that occurs at an implicit or unconscious level. Throughout my PhD, I learned a lot about the scientific process in general, the design of studies, statistics, the journal publication process, peer review and so on. It is a valuable foundation for science writing to understand the nuts and bolts of how the scientific enterprise works.

Because I was studying implicit bias over all those years, I find myself thinking on a daily basis about how it plays a role in journalism. It influences the kinds of stories we want to do with The Open Notebook, how we approach and how we source them.

Could you elaborate on this practice?

The underlying premise is that our backgrounds, circumstances, and personal experiences shape our perspectives. They influence how we tell stories and who we select as sources. It’s important to remain vigilant about this influence. Writing science with equity and inclusion in mind isn’t a one-time decision or limited to one-time events, simplistic policies or rules about source inclusion. It’s an ongoing practice, a commitment that lasts forever, and one that can always be improved upon.

We have published more than 50 articles that focus on diversity, equity and inclusion. Just recently we published a story about eradicating ableist language from our journalism. When I was growing up it was extremely common to say: “What a crazy idea”, “Oh that’s insane, that that happened”. We don’t even think of it as ableist. It is a process to learn to smoothly, easily, automatically replace that kind of language.

You published a book featuring a collection of Open Notebook articles: “The Craft of Science Writing”. It includes a chapter on the low earning potential of science journalists. Where do you think science journalism, as a whole, is headed?

It is a really tough time financially and that has meant job losses and disruption. It’s very hard for freelancers to make a living only doing journalism. This has been the story of journalism for the last twenty years, really. But science journalism is essential to society. It serves communities, policymakers, and individual people making decisions in their lives.

Currently, I am in Madison, Wisconsin, where the air quality has reached hazardous levels due to the Canadian wildfires. People need to make informed choices about going outside, and we rely on a well-informed society and public officials to provide appropriate guidance. At this fundamental level, we need science journalism, and we have to believe that there is a path forward.