Gülay Türkmen, sociologist at the WZB Berlin Social Science Center, has had many academic homes. Here she reflects on the scientific communities she experienced in Turkey, the US and Germany, communicating in different languages and her strategy to address sensitive issues.

“A lot of my colleagues from Turkey have to censor themselves.”

You’ve written about the challenges of academic mobility—uprooting your family, building a new home from scratch, and leaving again. What challenges does this lifestyle impose on the way you communicate about your scientific research?

I am originally from Turkey, and I completed my PhD in the United States. Then I lived in the UK for a short time, followed by the Netherlands and Germany. The biggest challenge is that these countries have different academic cultures. When you are trained in a particular way of studying and conveying research findings, it may not fit into another country’s culture. Moving frequently exposes you to both the best and worst aspects of each country and different ways of approaching things. Being open to and combining different approaches becomes a significant challenge.

Your academic homes have been Turkey, the United States, Austria, and Germany – how does science communication differ in these countries?

What I see in the US and Turkey is that when academics communicate, there can be negative repercussions from society, which include threats to some scientists. I know academics in the US who have stopped writing publicly, because they received death threats. Due to political polarisation things can escalate very quickly. Despite this, more scientists are speaking up in mainstream media channels in the US and the UK. I have not really observed German or Austrian academics communicating as actively. I don’t know why. In Germany, the level of political polarisation appears less severe, which would make it somewhat easier for scientists to express their views on controversial topics – except for the Israel-Palestine conflict, which is rather difficult to discuss in Germany. One thing to note about Germany is how much power full professors have over the PhDs and postdocs working in their projects. This sometimes results in a situation where the researchers working for a professor feel the need to reproduce that professors’ thoughts or refrain from challenging that professor’s line of thought. In the long run, this harms the plurality and variety of ideas conveyed to the public. Note, however, that my impression may be biased as I am not fluent in German.

Are different social media channels important in Turkey, Europe and the United States?

Actually, no. But you see subtle differences in how frequently these channels are used. In comparison to the US or Turkey, fewer people use social media in Germany. Of course, that partly goes back to the reluctance about digital transformation in Germany, which also has historical roots. People are wary of sharing their personal data as too many experienced mass state surveillance during the Nazi era. Personally, I find Twitter quite beneficial in the sense that I follow academic publications in my field or news outlets. I get most of my academic news through Twitter, actually. Other channels, like Instagram, TikTok and Twitch are less relevant for me, but are certainly useful in reaching younger people.

In your article “But you don’t look Turkish!“ you discuss a new wave of immigrants in Germany and the frustration of repeatedly explaining your identity. What challenges do Turkish scholars face in their science communication activities in Germany?

There are so many assumptions that play into people’s reactions. There are certain stereotypes about people from Turkey, which, as I said in the article, is understandable to a certain extent. After all, many –but not all of the –migrants from Turkey to Germany in the ‘70s came from rural, conservative areas. However, it becomes tiresome to constantly explain oneself, particularly during lectures or when writing. There is an expectation that Turkish academics in Germany must have been raised, studied, and educated in Germany. It is also assumed that they speak German. Why I don’t speak German often becomes another curiosity I have to address. Furthermore, there is an expectation for Turkish academics to study specific topics, such as migration. While I also study migration, this direction can limit options compared to international colleagues.

Would you approach speaking or writing about your research differently depending on the country?

I am quite active on Twitter in Turkish and write extensively about Turkish politics. Sometimes, I find myself choosing my words carefully, which is also the case in the US. Many colleagues are cautious with their words to avoid unnecessary hostility from audiences. Due to limited space, conveying nuanced ideas can be challenging within the platform’s character limit. If I am uncertain about the reaction my words may trigger, I prefer writing longer opinion pieces.

When I write in English I don’t feel the need to filter what I am saying as much, whereas in Turkish I always make sure to double-check. I read what I’ve written several times and think about whether it might create a problem. This goes for the US as well. In some of my classes there were particular issues that created polarisation amongst students. If you are teaching about the Middle East and the Israel-Palestine conflict, for example, you have to be sensitive about how you are saying things. Another example is the social construction of gender, which I taught in the rather conservative state of Virginia. Some students would protest the things I teach in class.

What about Germany?

I did not feel the need to be as careful during my lectures in Germany. Still, there are individual topics that create tension in different countries. When writing or talking about those issues, I tend to be a bit more sensitive. I am not the type who likes creating tension. I really try to reach as broad an audience as possible, and if I know that certain words will repel certain people, I try to opt for another word. If a different framing can help me reach those people whom I otherwise can’t reach, then I do that. If there are people in the audience who are indecisive about a topic, and if I can bring those people to actually start engaging with it by using more inclusive language, then I count that as a win. That’s how I approach things.

How do you pick the right outlet for your public sociology activities?

When I was in grad school, I followed outlets that interested me. I sent some of my pieces to them, and they got accepted. But of course, there were also instances where I sent out a pitch and never heard back. Then I tried another publication. Mostly, it’s outlets that I follow and enjoy reading myself. Once they know you, it becomes easier to get other pieces published. But it also happens the other way around. Some editors get in touch because they have already read something I’ve written elsewhere. They sometimes extend an open invitation, meaning if I write anything in the future, they will publish it or at least review it.

How important is academic freedom for science communication?

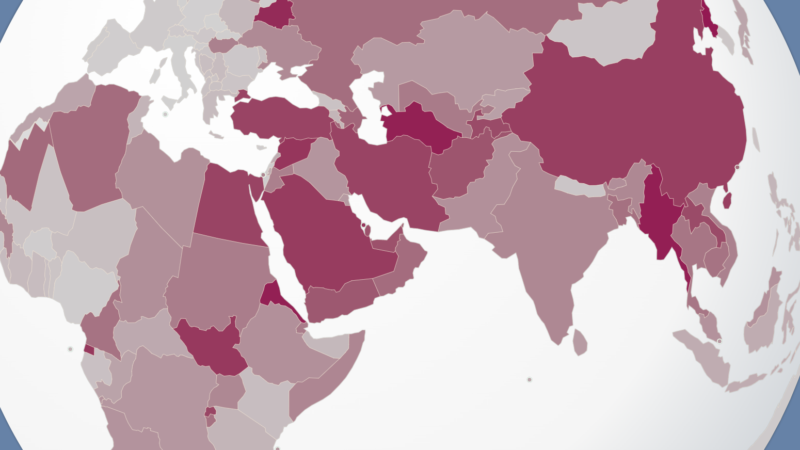

It is very important, of course. Let’s take Turkey as an example. Many of my colleagues from Turkey have to censor themselves. This is not only due to active censorship by the government but also because they are worried about imprisonment or losing their jobs. For example, when these academics apply for grants from a major Turkish funding body, they avoid using certain words in their project titles. It becomes a big problem in the long run. Even when these academics are interviewed by media outlets, they can’t truly speak freely. This also happens in Germany, but to a much lesser extent. For some of my German colleagues, it is not necessarily the government but their intellectual circles that exert pressure.